How Search-And-Rescue Dogs Work

When you're out hiking and you realize you've passed the same dead tree for the third time, and sundown is 20 minutes away, a dog looking for a game of tug-of-war might be your best chance at making it home. Search-and-rescue dogs are smart, agile and obedient, but their high "play drive" is what makes them look for a missing person through snow and rain, down steep rock walls and in crevices that would make a claustrophobic run screaming.

At its most basic, the job of a SAR dog has two components: Find the origin of a human scent and let the handler know where it is. In this article, we'll learn what SAR dogs do and how they do it, see what SAR training entails and find out what a real search-and-rescue mission is like.

At its most basic, the job of a SAR dog has two components: Find the origin of a human scent and let the handler know where it is. In this article, we'll learn what SAR dogs do and how they do it, see what SAR training entails and find out what a real search-and-rescue mission is like.

SAR Dog Basics

Experts estimate that a single SAR dog can accomplish the work of 20 to 30 human searchers. It's not just about smell, either -- dogs' superior hearing and night vision also come into play. Time is always an issue in search and rescue. In an avalanche situation, for instance, approximately 90 percent of victims are alive 15 minutes after burial; 35 minutes after burial, only 30 percent of victims are alive. While most avalanche victims don't survive, their chances increase exponentially when dogs are in on the search. Even in cases where victims are presumed dead, dogs are invaluable assets -- they locate the bodies so family members can have closure and give their loved one a proper burial.

SAR dogs can do a lot of amazing things, including rappel down mountainsides with their handler, locate a human being within a 500-meter radius, find a dead body under water, climb ladders and walk across an unstable beam in a collapsed building, but it's all toward a single end: Finding human scent. This may be in the form of a living person, a dead body, a human tooth or an article of clothing. SAR dogs find missing persons, search disaster areas for survivors and bodies and locate evidence at crime scenes, all by focusing on the smell of a human being.

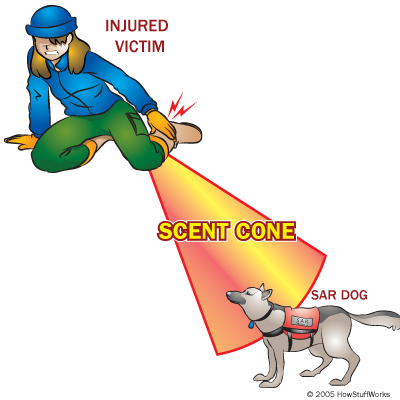

To people, this may seem like a difficult task. But to dogs, whose sense of smell is about 40 times stronger than a person's, it's a snap. To a dog, the scent of a human is as powerful and distinctive as the smell of a freshly baked apple pie is to a person. Human beings are smelly creatures -- they constantly shed dead skin cells called rafts, which contain bacteria and smell distinctly human. While it's impossible to know for sure, most experts believe that SAR dogs are smelling these rafts, which form a "scent cone" that the dog can easily pinpoint, when they're performing a search. Everyone's skin cells smell unique, which is how a dog can smell an item of clothing and search specifically for the last person who wore it.

cells called rafts, which contain bacteria and smell distinctly human. While it's impossible to know for sure, most experts believe that SAR dogs are smelling these rafts, which form a "scent cone" that the dog can easily pinpoint, when they're performing a search. Everyone's skin cells smell unique, which is how a dog can smell an item of clothing and search specifically for the last person who wore it.

While some dogs exhibit a stronger desire to scent than others, every canine out there has a powerful sense of smell. SAR dogs may be purebreds or mutts. Some handlers have a breed of choice, but any medium-to-large dog in good physical health, with decent intelligence, good listening skills, a non-aggressive personality and a strong play/prey drive (an intense, enduring desire to retrieve a toy) can potentially go into search and rescue. SAR dogs need to be big enough to successfully navigate treacherous terrain and push debris out of the way and yet small enough to transport easily. You actually don't find too many Saint Bernard search dogs these days, because they can be cumbersome. German shepherds are a popular SAR breed -- they're typically smart, obedient and agile, and their double-layered coat insulates against severe weather conditions. Hunting and herding dogs like Labrador and golden retrievers and border collies tend to be good at SAR work, too, because they have a very strong prey drive. Many people consider bloodhounds to be the best breed for tracking -- their giant ears and facial folds serve to collect and concentrate scent particles right at their nostrils, making their sense of smell extremely powerful and discerning. A bloodhound can pick up a trail weeks after other breeds can't find it.

This brings us to a distinction between types of SAR dogs: Some dogs track, while other dogs search.

SAR Specialties

Not all SAR dogs perform the same type of search. Some dogs are tracking (or trailing) dogs, and others are air-scent (or area-search) dogs. The types overlap, but the distinction between the two guides are the training process and how the dog participates in missions. Tracking dogs work with their nose to the ground. They follow a trail of human scent -- typically heavy skin particles that fall quickly to the ground or onto bushes -- through any type of terrain. These dogs are not searching, they're following: Tracking dogs need a "last seen" starting point, an article with the person's scent on it to work from and an uncontaminated trail.

For tracking, time is an issue. If a child disappears from a school playground or a inmate escapes from a prison, a tracking dog might be called in to follow the person's scent immediately after the disappearance, before other search groups and law-enforcement personnel contaminate the scent trail.

Air-scent dogs, on the other hand, work with their nose in the air. They pick up human scent anywhere in the vicinity -- they don't need a "last seen" starting point, an article to work from or a scent trail, and time is not an issue. Whereas tracking dogs follow a particular scent trail, air-scent dogs pick up a scent carried in air currents and seek out its origin -- the point of greatest concentration.

the vicinity -- they don't need a "last seen" starting point, an article to work from or a scent trail, and time is not an issue. Whereas tracking dogs follow a particular scent trail, air-scent dogs pick up a scent carried in air currents and seek out its origin -- the point of greatest concentration.

Air-scent dogs might be called in to find a missing hiker located "somewhere in a national park," an avalanche victim beneath 15 feet of snow or people buried under a collapsed building. Air-scenters might specialize in a particular type of search, such as:

- Cadaver - Dogs specifically search for the scent of human remains, detecting the smell of human decomposition gasses in addition to skin rafts. Cadaver dogs can find something as small as a human tooth or a single drop of blood.

- Water - Dogs search for drowning victims by boat. When a body is under water, skin particles and gases rise to the surface, so dogs can smell a body even when it's completely immersed. Due to the movement of water currents, dogs can seldom pinpoint the exact location of the body. Typically, more than one SAR team searches the area of interest, and divers use each dog's alert point, along with water-current analysis, to estimate the most likely location of the body.

- Avalanche - Dogs search for the scent of human beings buried beneath up to 15 feet of snow.

- Urban disaster - The most difficult SAR specialty, urban disaster dogs search for human survivors in collapsed buildings. They must navigate dangerous, unstable terrain.

- Wilderness - Dogs search for human scent in a wilderness setting.

- Evidence/article - Dogs search for items that have human scent on them.

Cadaver and water-search dogs are the only types specifically trained to scent for human remains, although all SAR dogs will alert to remains if they find them. In major disasters like the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995, the collapse of the World Trade Center in 2001 and the 2005 earthquake in Pakistan, air-scent dogs in all specialty areas assisted in the search for survivors. This actually led to problems for some of the dogs, because SAR dogs trained to find living people can become discouraged when they find only dead bodies. The dogs understand that live finds are preferable, partly due to their training, partly due to the reactions of their handler and partly because live people can usually give some form of feedback -- and the dogs crave feedback. At Oklahoma City and Ground Zero, handlers and firefighters hid in the rubble to give the dogs a living person to find so they could feel successful and get their reward.

In urban disasters, where people are trapped beneath precarious piles of debris, a dog's strength, confidence and agility are key. Even more important, though, is obedience: An out-of-control dog is a liability in search situations. This is where SAR standards come in.

SAR Dog Standards

The only national standards for SAR teams are the FEMA-certification standards for urban disaster work, which are very difficult to meet. In "The Art of Heroism," Wilma Melville, president and founder of the National Disaster Search Dog Foundation and part of a FEMA SAR unit in California, explains, "Wilderness searching is atmosphere-friendly to dogs. But in urban SAR, they're working in unnatural surroundings, amid rubble, pipes, 'tippy' things." Fewer than 100 dog/handler teams in the country are FEMA certified. Local SAR organizations have their own standards for "mission ready" qualification, typically based on guidelines developed by organizations like the American Rescue Dog Association and the National Association for Search and Rescue.

K-9 Search and Rescue Team, Inc., located in Dolores, Colorado, defines three basic skill levels. To become operational with this group, a SAR dog must pass each level of testing.

Level I: Basic Obedience

Level one addresses basic commands and temperament. To pass this skill set, the dog must be comfortable with non-threatening strangers and other dogs, pay attention to the handler while walking on a loose leash, walk through a crowd and amidst distractions without losing focus and obey basic commands like "sit," "down," "heel," "stay" and "come."

Test: While the handler is walking with the dog on a loose leash, they encounter one visual and one auditory distraction, such as a jogger running in front of the dog and a door slamming shut. The dog can be slightly startled, but he must not panic, bark or try to run away.

Level II: Canine Professionalism

Level two tests what K-9 Search and Rescue calls "canine professionalism." The dog consistently obeys basic commands and command combinations and shows no distress when separated from the handler. Passing this level means the dog can work effectively with another handler if necessary.

Test: The handler leaves her dog in a group of search dogs under the care of another handler. She puts her dog in a "sit" or "down" position and tells the dog to "wait." The handler then walks at least 30 feet away, where the dog cannot see her. Several different handlers then rotate into the caretaker position, watching over all of the dogs. This goes on for at least 15 minutes. Each dog must remain in the "sit" or "down" position without any additional command until his handler returns.

Level III: Physical and Mental Ability

Levels one and two test for the obedience that is necessary in a search situation. Level three addresses the physical and mental rigors of the work. Can the dog handle SAR conditions and expectations?

To pass this level, the dog must navigate a tunnel, climb an A-frame with a minimum 45-degree incline on each side, get into a tractor bucket with his handler and be lifted at least 10 feet without trying to jump out, and sit in cart pulled by an ATV or snowmobile without trying to jump out. He also travels in a boat without trying to jump out, confidently approaches a running helicopter and accepts being lifted into the air while wearing a harness.

Tracking

The K-9 Search and Rescue Team has additional standards for tracking dogs: Level III is wilderness tracking, Level II is suburban tracking and Level I is urban tracking. The urban tracking qualification involves the following test:

A person (the target) lays a 1/2-mile to 1-mile track (moves from one point to another) in a highly populated, high-traffic area of a city. The target crosses at least two intersections, makes at least three right-angle turns, goes down two blocks of alleys and leaves a scent article in the alley. Once the target lays the track, another person crosses that track in at least one place, adding another scent trail to throw the dog off. Thirty minutes after the target is at his end position, the handler places the dog on the scent trail. The dog must complete the trail (find the target) in no more than the time it took for target to lay the track. The dog faces distractions throughout the test, including loose dogs and cats, other SAR teams and heavy machinery in operation, and confronts obstacles, including barbed fences and brick walls the dog must find a way around (or over) in order to stay on the trail.

A dog and his handler have to train hard to pass the qualification standards of search-and-rescue work. The training starts when the handler identifies the ultimate reward for the dog. This is usually pretty easy to figure out.

SAR Dog Training

It may seem like a dog obsessively focused on play would make a poor working dog, but for search-and-rescue work, this is actually an ideal trait. A dog that will chase a tennis ball for hours would probably walk through 10 feet of snow, over a mountain and down a rocky embankment that makes his paws bleed to find it -- and get someone to throw it for him again. For this SAR dog, locating the origin of a human scent would mean a game of "find the ball." This is the basis of SAR training: associating human scent with something the dog wants very badly.

The central jobs of a SAR dog are to find a human scent ("find it") and effectively alert his handler to its location. SAR training assures that a dog can complete these tasks in all conditions, regardless of weather or distractions. Depending on the dog's specialty area, his core training may also include the recall-find ("show me"), in which he finds a person, returns to his handler and then leads the handler back to the person, or victim loyalty, in which the dog stays with the person and alerts his handler by barking.

Most SAR dogs live and train with their handler, and it takes about 600 hours of training for a dog to be field ready. Sometimes, SAR associations adopt dogs from shelters for the specific purpose of training them for search and rescue, and they'll train at a special facility and then be paired with a handler. Wilma Melville of the National Disaster Search Dog Foundation combs animal shelters looking for dogs with "a great willingness to hunt for a tossed toy, together with a couple of traits that might turn other shelter adopters away: boldness and a high prey drive" [ref]. Potential SAR dogs should also be obedient and attentive, have a friendly temperament (they're going to be working closely with strangers and other dogs in a search situation) and possess a strong desire to please. Obedience and focus are crucial. A handler must be able to control her dog at all times and in all situations. But a SAR dog who can't think for itself is useless -- air-scent dogs work off-leash, so the handler won't always be nearby to give commands. The ideal search dog can solve problems on his own but is always aware of his handler.

The general approach to training a dog for search and rescue is no different from training a dog to complete any other task. The first step is to figure out which reward the dog will work for, and always immediately reward the dog when he does the right thing. Dogs don't do charity -- they'll only work for the reward. In the course of training, you associate that reward with each thing you want the dog to do -- in this case, locate human scent and alert you to it in a uniform way. The training starts out with very simple tasks and gets progressively more complex as the dog completes each level.

Example: Avalanche Training

Training a dog to "find it" is more about directing a dog than teaching her. Dogs have a natural inclination to locate scents -- SAR training involves letting a dog know which scent you'd like her to locate and where this scent might be. Each time the dog completes a task, she gets her reward. Let's say this particular dog works for games of tug-of-war with a stinky sock.

For avalanche training, the first step is simply to get the dog to search under the snow. The handler digs a hole in the snow, and a second person holds the dog while the handler makes a big show of running away and jumping into the hole. The dog is watching the whole time, typically straining to follow the handler. When the assistant releases the dog, she runs to find the handler. When she finds the handler, they play tug-of-war. This gets the dog interested in finding people.

The next step is to increase the amount of time the assistant holds the dog. This increases the level of memory and attention span required to find the handler. First, the assistant holds back the dog for, say, five seconds. The dog finds the handler and gets to play tug-of-war. Then the assistant holds the dog for 10 seconds, then a minute, then five minutes, and so on. Each time the dog finds the handler (which is pretty easy, because she's watching while the handler hides in the same hole time after time), she gets her game of tug-of-war.

By this time, the dog is totally into the game, so the handler adds another complication: An assistant covers the handler with a few inches of snow. This time, when dog runs to find the handler, she can't see him, but she can smell him. So she starts digging. When she finds him, she gets her stinky sock. In this way, the dog discovers that people can be under the snow and that human scent emanating from snow means that digging in that spot will reveal a person who might play with her. Then, the handler and assistant change places, and the handler manages the dog while the assistant hides under the snow. By this stage, the game is well established, and the dog knows what she needs to do to get her reward.

Finally, distractions are added to the game. The dog begins playing the "find it" game with people and dogs milling about the area and avalanche-search equipment, like poles and shovels, lying around in the snow. In a real avalanche search, distractions are everywhere, and the dog must be able to focus on the search despite the chaos around her.

Once a dog really gets the game of "find it," training her to alert to the find is pretty easy. Dogs typically have a natural alert that handlers need only reinforce and encourage. In the case of avalanche finds, dogs usually dig at the area where they detect human scent. If a reward immediately follows a correct alert (meaning the dog is digging in the right place), the dog will continue to alert in that manner.

A field-ready SAR dog can focus on the task at hand -- whatever his handler is commanding him to do -- no matter what. The dog maintains vigilance and dedication to the search through all types of weather conditions and navigates treacherous terrain without losing confidence.

A SAR dog will walk across a rope bridge if need be, lowering his center of gravity to minimize the swaying. The dog will ignore a Big Mac lying in the middle of the woods and will refrain from sniffing another SAR dog's butt if he's on a "find it" command. This level of concentration is not about taking work seriously -- it's about taking play seriously. Whether it's a training exercise or a real search, it's all a game to the dog.

Handler Training

On average, a SAR handler spends about 1,000 hours becoming field-ready. She learns how to properly train a dog to find and alert and trains herself in land navigation, weather patterns, radio communications, map and compass skills, wilderness survival and advanced first aid including CPR.

Hannah Harris and her German Shepherd, Grace, trained for SAR in Maryland. They spent about 48 hours a month training. Harris notes the level of multitasking required for a handler to clear their sector:

It's vitally important that you search your own sector thoroughly and that you know where you are at all times in case your dog alerts ... but doesn't do a find. An area can be identified for further searching if several teams alert toward one spot, even without finding anything. Knowing exactly where you are sounds simple but our team trained somewhere different every week, so that we didn't get a chance to know the area very well and had to rely on our topo maps. I have a good sense of direction that helps me do wildlife research but it was hard for me to let that go and trust my compass. Your map and compass are more reliable than your gut, particularly when it comes to night navigation. At night, searching conditions are better for the dogs because of the way the air moves, but it's very difficult to keep your footing, watch your dog with a flashlight, AND keep track of where you are on the map and in what direction you're moving. Most real searches have a dog team and a walk along to help with the navigation, but your walk along may or may not be that reliable and you have to be able to do it all by yourself to qualify as operational.

SAR Dogs at Work

SAR teams are on call 24 hours a day, seven days a week, 365 days a year. Dogs often accompany their handler to work and on vacation in case a call comes in from law-enforcement authorities. Typically, a police unit alerts a SAR organization to a case, and the SAR organization then alerts its team members. The case might be a missing child, a group of hikers who never arrived at their camp site, a bombed building, an earthquake, an escaped convict or a new tip in a crime that places a victim's body in a particular lake.

Once alerted to a call-out, the dog/handler team loads up its equipment, which may include severe-weather gear, ropes and harnesses, radios, compasses, maps, food, water and other items that come in handy on a search. If the call-out is for an avalanche search, transportation might involve a helicopter. If it's a wilderness search, the team usually drives to the base location and then hikes or rappels to the area of the search. If the search is for a drowning victim, the handler and dog arrive by boat at the area of interest.

Once at the scene, the dog's obedience is fully tested. Distractions are everywhere -- people and dogs searching, hysterical family members, reporters, flood lights, bullhorns. The SAR unit leader is in charge, reporting to the head law-enforcement authority or search authority at the scene. At a large search, a SAR group may set up a base camp complete with radio communications, rest areas and search advisors. The SAR leader gives each dog/handler team a location to clear. If the dog shows interest in a particular spot but does not do a full alert, the handler notes the location. If the dog gives a full-blown alert, everyone mobilizes. In a water search, divers hit the water; in an avalanche search, every available hand digs in the snow; in a wilderness search, people might work to pry rocks out of the way of a cave opening to find what may be the missing hiker. While this is going on or immediately afterward, the dog and his handler are off to the side playing tug-of-war (or whatever the dog's reward of choice is) so the dog knows he won the game.

Even if the missing person turns out to be dead, and the family is present, the handler will discreetly play with the dog. As long as search-and-rescue remains a game, the dog will happily do his job until his handlerdecides it's time for retirement.

Retirement

Typically, a dog retires when he can no longer handle the physical rigors of the work. Charles Melvin, Team Leader for the K-9 Search and Rescue Team, reports that his team's dogs usually retire when they're eight to 10 years old. In "The Art of Heroism," Anthony Fernandez, who serves with his dog Aspen in the Metropolitan Dade County Fire Rescue Department, explains that "SAR is a young dog's game. It can be stressful." Urban disaster work in particular is hard on both the dog and the handler. Some SAR dogs retired early after the World Trade Center attack due to extreme stress and health problems from searching at Ground Zero. A dog might retire from disaster work and go into a more laid-back specialty such as wilderness search, or he might retire from the job completely.

When a SAR dog retires, he usually lives out his retirement with his handler. If the handler can't take care of him any longer, there are organizations that will find new adoptive homes for retired search dogs. In either case, the dog enjoys a life of fun, games and leisure, a much-deserved reward for a career of fun, games and public service.

From:HowStuffWorks.com

Ontario Dog Sports

Ontario Dog Sports

Reader Comments